It was a dark day when I realised that everything I had ever been taught about how to revise was WRONG! Over the last century, neuroscience has proved what I guess I was already starting to realise…

we don’t learn best by reading our notes on one subject, in the same quiet spot, for an hour at a time, then going online to reward ourself. Cramming and reading notes right before our exam means the info won’t stay in our brain long-term. Pulling an all-nighter before an exam is truly a disaster. We shouldn’t learn the material thoroughly, then do a past paper and send it to the teacher for feedback. What?!!!! Like I said, dark days.

But then, I kind of knew that those things didn’t work for me, but I thought that was because I was dyslexic, because I was a bad student. Turns out, my awful memory meant that I was forced to adopt more effective study habits. I got great grades, but always felt like I was a freak or a fraud for the weird way I studied.

In the years since I’ve voraciously read the research, I’ve seen the brain scans. They showed better results with counter-intuitive methods. But why we would learn better by mixing things up, by taking breaks, spacing things out, learning in different places, at different times, for shorter periods, but over long periods of time? Why did I need to thinking about why it was important to me and link it to things I already knew? The scientists and researchers said one thing. Teachers and the internet said the opposite. Who to believe?

Then, whilst studying to be a dyslexia assessor, I listened to a super boring lecturer who took it right back. He asked us to consider the 1.8 million years that our ancestors hunted and gathered, compared to the hundreds of years that we have lived as we do now. For at least 90% of human history we learned which plants heal, which ones you can eat and which kill. We learned to interpret the stars, the weather, the tracks of animals. We learned this in different contexts, in short bursts, with breaks, it was spaced out and very relevant.

We didn’t learn by sitting down, reading and writing. Reading and writing are perhaps only five and a half thousand years old and books are only two thousand years old. Most ordinary people in the U.K. didn’t learn until the last 300 years and in 18th-century Europe, the new practice of reading alone in your bedroom was considered dangerous and immoral! Even in 1950 the world’s adult literacy rate was only just over half. We may think we’ve evolved, but our brains simply haven’t caught up.

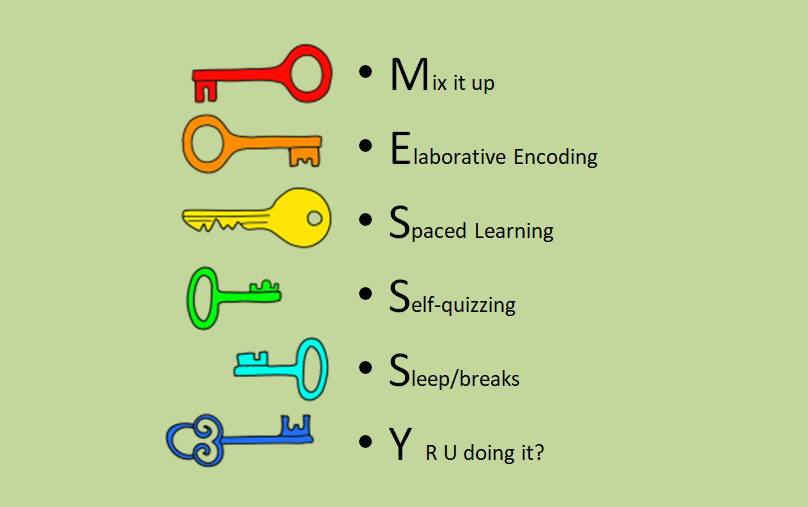

This really helped me to understand why learning works best when it is ‘messy’. Here are my 6 keys to effective revision:

Mix It Up

Mix up topics: Research has shown that even though it feels more satisfying to focus on one topic, we learn more when we interleave topics.

Mix up methods: If we always learn and test ourselves in one way, we tend to fall victim to the fluency illusion.

Mix up times and locations: Learning can easily become context-dependent and so if we’re not able to study at the exact desk we will sit at for the exam, we would be better varying things. For example, a few years ago I wrote a TED talk about how we would wreck our ecomomy if we don’t rip up the school rulebook. I used a variety of memory techniques, but learned it in the car on a few long car journeys. Trouble is, I can now only deliver it whilst driving – the noise of the engine, the interior of the car, the feel of the gear stick and the vibrations of the car are what I have associated this speech with. Doh!

Elaborative Encoding

This is a very posh term to describe the process of linking new information to known information, through working with it and rehearsing it. This is why other people’s flashcards and mnemonics are never as effective as the ones we create ourself. We need to be the one who draws the mindmap, makes up the acrostic or papers our room in post its. But we may need help over the years learning to do it.

We remember stuff that is odd, funny, vivid, relevant, personal or disgusting. The more memorably and deeply we embed new knowledge, the less time we will need to spend revising it. And vice versa. Don’t embed it well and we will have to revise it over and over and over. Experiment with a range of memory techniques and methods of learning to find out what works best for each of us.

Spaced Learning

We remember things best that have meaning over time, so we need to spread learning out, rather than cram.

Imagine a meadow: if we walk through, trampling down the grass once, but then never walk that way again then the grass will simply spring back up and we won’t be able to find that same route. If we walk the same route the next day, then a few days later, then a week later, then a month, then a couple of months later, it does not take up much time but it preserves that path.

Spaced learning is originally based on Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve. Rather than ‘cram’ once for half an hour on one topic, my suggestion would be that the same amount of time is spent on revision of a topic, it is just spaced out, e.g. 5 minutes one day, then 5 minutes the next day, then 5 minutes a week later, then 5 minutes a month later, then 5 minutes two months after that, then 5 minutes before the exam.

There is debate about what the perfect revision intervals are. Some researchers say revising immediately after, 24 hours later, one week later, one month later, three months later.

Pimsleur’s intervals for language learning are 5 seconds, 25 seconds, 2 minutes, 10 minutes, 1 hour, 5 hours, 1 day, 5 days, 25 days, 4 months, 2 years.

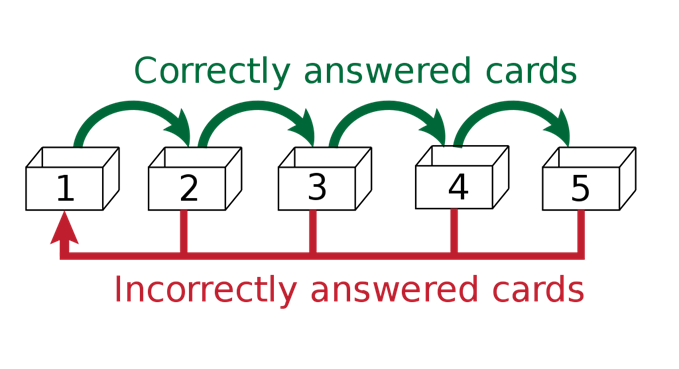

I like Leitner’s Learning Box where flashcards are sorted into groups according to how well we know each one.

We try to recall the solution written on the back of the flashcard. If we succeed, we promote the card to the next group. If we can’t remember we send it back to the first group. Each succeeding group has a longer period of time before we revisit the cards.

Self-quizzing

We are taught to test ourself once we have learned it. That feels good. But it turns out that we get much better results if we test ourselves frequently and mix up topics. It may make us feel rotten but we get better feedback and don’t fall into the fluency illusion. My favourite is to take a blank piece of paper and jot down/draw everything I know about a particular topic.

Try to keep it fun. Make a quiz for family/friends, turn it into a game or use a free app like Study Stack which takes our flashcards and turns them into games. Some rules for max results: get immediate feedback about what the right answer is. Make sure we always guess an answer, even if we don’t know. It means that we’re emotionally invested in the answer. If we answer wrongly our brain will get annoyed and so remember the correct answer more.

If we take a quiz BEFORE we learn about an important topic, our brain will be convinced of the usefulness of this information and primed to be alert to key vocab and facts.

Sleep/Breaks

Sleep is the time when our brain sorts through everything we’ve learned and so it is crucial to get enough and good quality sleep. A particular problem is that teenagers’ optimum sleep patterns seem to be two hours later than adults and children, but schools and exams don’t take this into account.

We also need lots of short, wordless breaks. Read about some of the reasons here.

There is lots of great research about the amazing benefits of naps (particularly after we’ve studied). But it is crucial to research the optimum timings (what time and for how long) depending on our own circumstances.

Y R U doing it?

This is both true of the information we are trying to learn and also the exam we are trying to pass. We need to know the relevance, otherwise we are unlikely to remember it. Teenagers tend to live in the present and so it is vital that we help teenagers to think about the future. I think everyone should have a vision board, so we know what success for us looks like and we have something amazing to aim for, to keep us motivated in hard times.